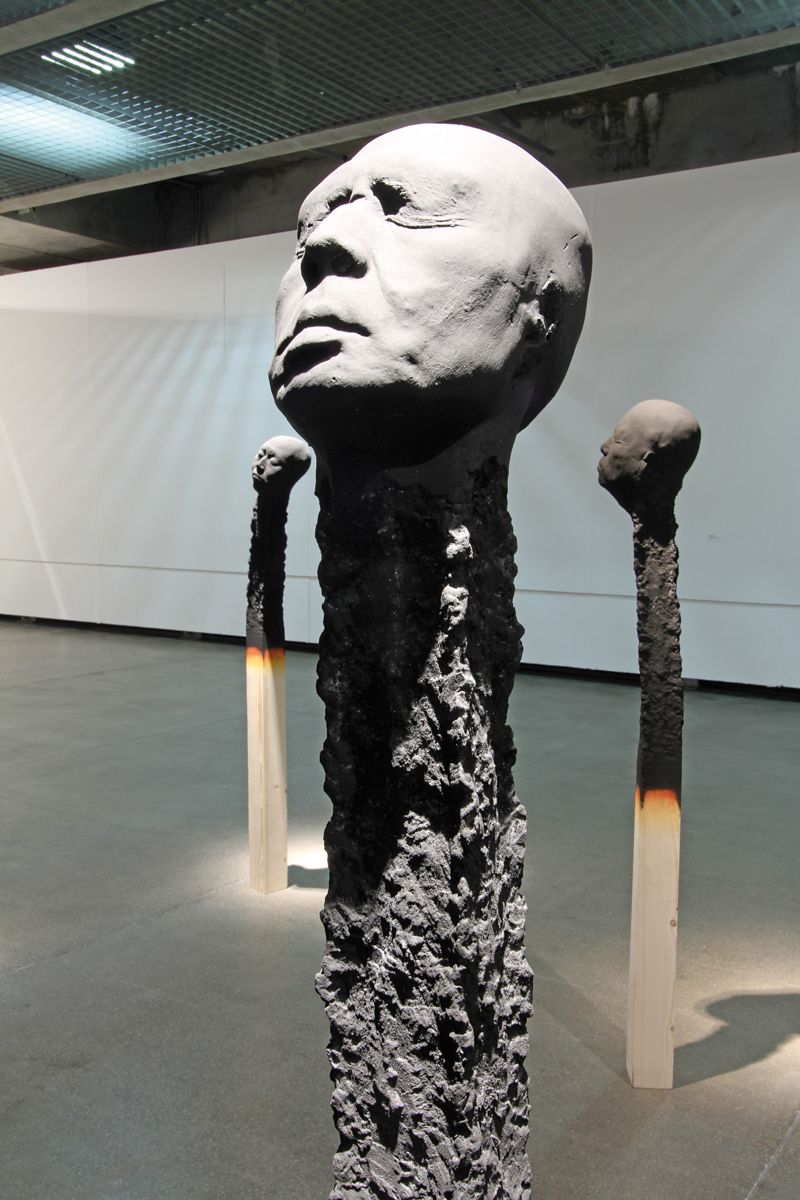

Introspective, Symbolic, and Fragile: these three words encapsulate the essence of Wolfgang Stiller's profound artistic evolution. A master sculptor who delves deeply into themes of human impermanence and mortality, Stiller's creations are both evocative and thought-provoking. His iconic "Matchstickmen" series, born from his involvement in a film project about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, poignantly reflects the fragility and fleeting nature of human existence. These sculptures serve as a metaphor for the exploitation of human resources and a stark reminder of life's transient beauty. Stiller's work is imbued with a deep philosophical undertone, shaped by personal experiences and his exploration of Buddhist teachings during his time in China. Despite the pressures of commercialism in the art world, he remains steadfast in his artistic integrity, creating work that transcends temporal and political boundaries. His sculptures are not just visual art but profound commentaries on the human condition, urging viewers to reflect on the ephemeral nature of life and the importance of living meaningfully.

We’d like to delve into the beginning of your career and your education. You studied communications design and later pursued art studies. What influenced you to change your path, and how have the years of studying inspired you to embark on your journey as an artist?

When I started studying graphic design, I already paid more attention to drawing and painting. I also started a short animation movie. I studied there for about two years when a friend of mine brought a well-known gallery owner to my studio. He suggested that I study at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, which was the most prestigious art academy in Germany at that time. He came again with a professor, Gotthard Graubner, who was a well-known painter. Graubner selected several of my works and handled the entire application process for me. I wasn't really excited, but I thought, why not? A few months later, I received a call informing me that I had been accepted at the academy. So, I transferred to the academy and studied fine arts. However, I was never really happy there. If I learned one thing there, it was what I didn’t want. I was really disappointed by the lack of real exchange between the students, and I felt alienated. But I learned to stand my ground. Unfortunately, I can't say I was inspired by studying there. In the final two years, I hardly went there anymore and instead stayed working in my studio. I started working as an assistant in Tony Cragg's studio and learned a lot from his older assistants about the process of making molds and other sculpture techniques. That was a far better education than what I was offered at the academy. It is something I would recommend to every young artist: find a job at an artist's studio and learn how things are done.

Wolfgang, your work delves deeply into themes of human impermanence and mortality. Could you elaborate on how your personal philosophy and experiences have influenced this exploration, perhaps beginning the “Matchstickmen” series?

The Matchstickmen series started after I was making several dummies for a movie about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, or more specifically, about a German (John Rabe) who saved many Chinese people during the occupation. Many civilians were killed and decapitated. There is a famous photo showing chopped-off heads on a tree trunk. After the movie production was finished, I played around in my studio with the head molds I had from this production. Initially, I had those heads on bamboo poles like stacked trophies, something the Mongols did in the old days to frighten and crush resistance. Little by little, they ended up on squared lumber and finally became the Matchstickmen. The initial idea was to create a metaphor for the waste and exploitation of human resources, which later was accompanied by the fragility of our human existence and the fact that we all have to die. They are supposed to serve as an encouragement and reminder to use our lifetime in the most satisfying and meaningful way. Every time we see a loved one, it could be the last time we see that person. Life is so fragile and can end at any moment, which is something we should keep in mind at least once in a while.

Drawing has been noted as your initial medium, reflecting the subconscious of your psyche. How does this subconscious expression manifest in your artwork, and how do your drawings influence your sculpture creations?

I'm not sure if I would call it an expression of my subconsciousness. Creating sculptures is not a very spontaneous process. Everything has to be planned in advance with most of the materials. It's not like painting, which allows you to correct and change things easily. Once something is chopped, it can't be undone. What I love about drawing is the raw and spontaneous aspect. I never really plan what to draw unless it is a sketch for a sculpture. It's a bit of entertaining and surprising myself. I like to tell little stories to myself when I draw, just to entertain myself in that very moment. My drawings sometimes become ideas for a sculpture. For example, "Samsara," one of my favorite works, was first drawn 20 years ago. I thought it could become a nice sculpture one day. I knew it should be made from bronze, but since I didn't have the resources when I was younger, I waited patiently. However, it is actually rare that my drawings influence my sculptural work. I really enjoy the lightness of drawing. If a drawing doesn't turn out well, I can easily throw it away and start another one. It's not so easy to discard something that took a long time to build and was expensive to produce.

Your experiences as a gravedigger and the loss of close friends at a young age led you to explore Buddhism. Can you share how these experiences shifted your mindset and influenced your artistic perspective? Tell us more about what influenced you in your time in China.

Through personal experience and observations, I realized how fragile life actually is. The confrontation with death got me interested in Buddhism, as it addresses this subject in a very specific way. Death is something we normally don’t want to talk about. It's something in the far future and mostly happens to other people. Isn’t that the way most of us handle this subject? There are so many challenging subjects for an artist within the Buddhist view and philosophy. It's a vast resource for mind-blowing thoughts. It's very disturbing as well, since it goes against a lot of things we have deeply established within us. Many of my later works are inspired by thoughts and reflections on Buddhist views.

Reflecting on your experiences in Berlin before and after the fall of the wall, how did these historical events shape your creative expression, particularly concerning artistic freedom? How do you navigate contemporary challenges like political correctness in your work?

I never react to political or historical events in real time. I actually really dislike when art becomes a propaganda tool for a political opinion because that’s what it always boils down to. If I want to express my dislike about a certain situation, I go out on the street and demonstrate, but I never let it interfere with my art. Those things are always momentary and subject to change, like everything else.What interests me in art are subjects that will be relevant now as well as 100 years from now—eternal subjects, so to speak. To me, there is nothing more boring than seeing an artist creating work to criticize, let's say, Trump. Who will care about this in 50 years from now? My work always develops from what I have done before, and I don’t change course just because another war broke out or because I don’t like the ruling political party. I like when art is socially relevant without judging. Everyone is judging and expressing their opinions these days. Look at the newspapers; it’s pure opinion without giving me the choice to just inform myself and form my own opinion based on facts. So I prefer art that leaves space instead of trying to pull me in a specific direction. Political correctness these days is pretty disturbing, and I couldn’t care less about it. So-called political correctness today is a debate killer. There is no space left for a serious discussion about certain subjects.

Do you believe there's a superior medium for exploring and sharing ideas—visual art, text, or speech? How do you decide which medium best suits your expression?

No, I don’t think there is a superior medium in art. I love all of them, but I am not good at all of them. Therefore, I am already limited in the choices I have. I definitely don’t want to be one of those artists who do a video, some drawings, paintings, and sculptures in one show and call it an installation. I have seen many such shows, and none of the individual works has any quality on its own. Maybe the artists hope the totality will make up for the lack of quality in each medium. I love movies, and when I see poorly made videos by contemporary artists, I just want to run away. Personally, I don’t trust any artist who can’t draw, since drawing is the most simple and honest expression. I am a bit old-fashioned in that I want to be the actual producer of my works. Many artists today lack skills and outsource their ideas to companies that can execute visual products. I prefer to stick to a limited number of mediums—the ones I can actually master myself.

Commercialism in the art world often prioritizes profit over artistic integrity. What's your stance on this issue, and how do you balance commercial success with maintaining artistic authenticity?

Unfortunately, that is very true these days. When I started working as an artist in the 80s, the situation was quite different. It only changed when the big money from the stock market came into art. Everyone with a six-figure income started to buy art, not because they really liked it, but because it was a trendy thing to do. I think that’s when artists started to bend toward the market rather than following an inner search, or whatever you want to call it. When I was young, I definitely wanted to have shows in museums and be in important collections—to make a name in the art world. It was not at all about making money. I was actually very naive about it. I just never thought about how I could feed myself 30 years later. It took me around 30 years to make a decent living from my work. I have certain works that are more collected than others— I guess that’s true for almost every successful artist. Every successful artist has a kind of bestseller, which doesn’t necessarily represent their entire body of work. I am okay with that since I can always work on new stuff without worrying about paying my bills. It gets difficult if an artist creates works just to satisfy the market. But in the end, every artist has to decide for themselves.

Your choice of materials is integral to your artwork. Could you discuss how different materials impact the meaning and significance of your pieces?

Basically, I have two different approaches. Either I have an idea for a specific work, which kind of dictates the material, or I look for the best material that would benefit the most. The other approach is that I stumble upon some material, perhaps by chance, and the material immediately gives me an idea for a new work. This happened more often when I did a residency and was away from my regular studio production. For instance, I stayed for two months in Taiwan on a residency. While I was exploring the neighborhood, I found these shrimp traps made from plastic, which gave me the idea for a chandelier.

Looking ahead, what are your aspirations for your artwork, and what legacy do you hope to leave behind as an artist?

I am not the type of person who looks too far ahead into the future, let alone considers what will happen after I'm gone. My focus is on coming up with fresh ideas for new sculptures, and I find joy in people collecting my works because they connect with them in some way. As for my legacy—do I care? Not really. Why would I care once I'm dead? There's no chance to experience it anyway.